|

|

|

IMMEDIATE ASSIGNMENTS: IMMEDIATE ASSIGNMENTS:

• For TH, 5/9: Group Presentations (in order):

#6: LOST: The Adventure Home

#4: Sex Education: The Nudes & the Prudes

#5: Gardens & Some Doofs

Remember: give me your hardcopy outline(s)/"script" before your presentation (i.e., the beginning of class); OR: email me the file(s) or cloud link (to a PPT, etc.) by 10:00 a.m. the day of your pres.!

—Also, if you're in the first group to go, be in class early enough to set up any AV stuff by 11:00 p.m.

• Uploaded to CANVAS by TU, 5/14, 5:30 pm: Final Essay

• Gardens: Tom's MOTIFS •

• MAP to the Gardens •

• Presentation Groups (and/or see Canvas Groups!) •

|

|---|

(If you can't laugh at your favorite authors,

you shouldn't be an English major!) |

|

|---|

NOTE: I am intentionally brief, even abbreviatory, in the following NOTES because I mean them

to function as reminders & sources of review rather than to serve in lieu of coming to class: they DON'T.

However, this page has a further usefulness: by "Commentary," I mean that some points in these class notes

are expanded upon (and re-organized) in ways that our limited class time—and my rather manic teaching

style—disallowed. . . .

Further Note: Highlighted author names are linked to each

respective author's entry on my Native Authors & Readings Links page, for further research on your part.

| = = = = TIOShPAYE (permanent small groups) = = = = |

|---|

T. #1:

Connor Beck

Ashe Franta

Lisa Fruehling

Brittani Perez

Leah Stirrup

|

T. #2:

Phoebe Boname

Jordan Harper

Shaadira Morones

Lilian Nguyen

Sophia Vinje

|

T. #3:

Drew Baldridge

Alex Clinger

Julia Klug

Val Villegas

Emily Yelden

|

T. #4:

Vera Butterfield

Sarah Danielson

Emma Gillette

Leah Larson

Kennedy Sommerer

|

T. #5:

Hailey Brundage

Jocelyn Garcia Gutierrez

Rowan Havranek

Angelina Pattavina

Mikaela Waggoner

|

T. #6:

Kayla Barnes

Isabella Lone Hill

Sydnee Lybarger

Sarah Nass

Julia Rucker

|

|

Note: This list has been replicated as Canvas "Groups"; in fact, I used Canvas's "synchronistisizer"(!) function to create these groups. From there you can email your fellow group members at any time—especially helpful for your group presentation.

|

TU, Jan. 23rd:: Syllabus, etc.— TU, Jan. 23rd:: Syllabus, etc.—

|

"What Made the Red Man Red" (from Peter Pan [1953])

Why does he ask you, "How?"

Why does he ask you, "How?"

Once the Injun didn't know

All the things that he know now--

But the Injun, he sure learn a lot,

And it's all from asking, "How?"

Hana Mana Ganda--

Hana Mana Ganda--

We translate for you--

Hana means what mana means,

And ganda means that, too.

When did he first say, "Ugh!"

When did he first say, "Ugh!"

In the Injun book it say,

When the first brave married squaw,

He gave out with a big "ugh"

When he saw his mother-in-law--

What made the red man red?

What made the red man red?

Let's go back a million years

To the very first Injun prince--

He kissed a maid and start to blush,

And we've all been blushin' since--

You've got it from the headman--

The real true story of the red man,

No matter what's been written or said--

Now you know why the red man's red!

|

|

SURE YOU CAN ASK ME A PERSONAL QUESTION

How do you do?

No, I am not Chinese.

No, not Spanish.

No, I am American Indi—Native American.

No, not from India.

No, not Apache.

No, not Navajo.

No, not Sioux.

No, we are not extinct.

Yes, Indin.

Oh?

So that's where you got those high cheekbones.

Your great grandmother, huh?

An Indian Princess, huh?

Hair down to there?

Let me guess. Cherokee?

Oh, so you've had an Indian friend?

That close?

Oh, so you've had an Indian lover?

That tight?

Oh, so you've had an Indian servant?

That much?

Yeah, it was awful what you guys did to us.

It's real decent of you to apologize.

No, I don't know where you can get peyote.

No, I don't know where you can get Navajo rugs real cheap.

No, I didn't make this. I bought it at Bloomingdales.

Thank you. I like your hair too.

I don't know if anyone knows whether or not Cher is really Indian.

No, I didn't make it rain tonight.

Yeah. Uh-huh. Spirituality.

Uh-huh. Yeah. Spirituality. Uh-huh. Mother

Earth. Yeah. Uh-huh. Uh-huh. Spirituality.

No, I didn't major in archery.

Yeah, a lot of us drink too much.

Some of us can't drink enough.

This ain't no stoic look.

This is my face.

—Diane Burns, c. 1989 |

** Several of our readings (will) have already mentioned the Trail of Tears, the Little Bighorn, Wounded Knee, etc., and so--

| MASSACRES & TEARS—(A Few) Dates that Live in Infamy |

|---|

| —with an emphasis on events that have become "rallying points" in

contemporary NatAmer lit.— |

| 1830: Indian Removal Act |

federal policy to (forcibly) move southeastern tribes west of the Mississippi—incl. Choctaw, Seminole, Creek,

Chickasaw, and Cherokee; thus Oklahoma and environs was originally the "Indian Territory" |

| 1838-1839: "Trail of Tears" |

forced march of the Cherokee from Georgia, etc., to Indian Territory (Oklahoma); plus, a similar fate for other southeastern tribes (the

Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek [Muscogee], & Seminole—although some of the latter got to stay in Florida to root for FSU football!) |

| 1864: Navajo "Long Walk" |

forced march of the Navajo to Fort Sumner in New Mexico; more than 2,500 perish; returned to homeland

in 1868 |

| 1864: Sand Creek Massacre |

slaughter of approx. 140 Cheyenne & Arapaho (incl. women & children) at Sand Creek (Colorado); the

Cheyenne chief Black Kettle survived, until-> |

| 1868: Washita River |

Custer's Seventh Cavalry's massacre of Cheyennes led by Black Kettle in Indian Territory (Oklahoma);

approx. 100 Native dead, incl. women & children |

| 1868: Fort Laramie Treaty |

THE "broken treaty": prelude to the Little Bighorn, the Black Hills land controversy, and the American Indian Movement (AIM) |

| 1876: Battle of the Little Bighorn |

Custer's Seventh Cavalry versus the Lakota & Cheyenne, led by Sitting Bull (Tatanka

Iotanka [Hunkpapa Lakota]) & Crazy Horse (Tashunka Witko [Oglala Lakota]) |

| 1883-1934: Federal ban on the Lakota Sun Dance | —and comparable restrictions on other tribes' major ceremonies standard during this same period |

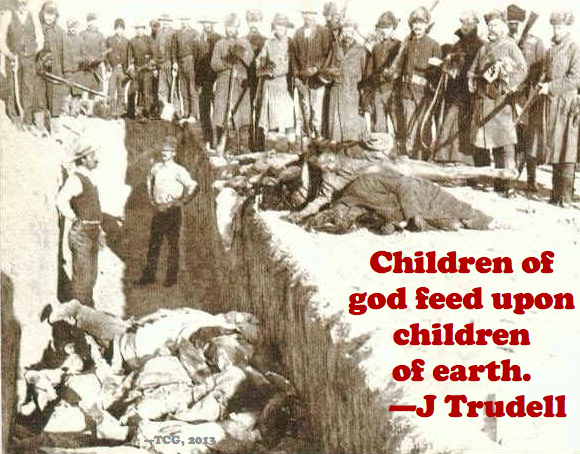

| 1890: Wounded Knee Massacre |

slaughter of largely unarmed Lakota Ghost Dance adherents near Pine Ridge (South Dakota);

Native dead: approx. >300, incl. many women & children |

| A decent, semi-brief history of

The Ghost

Dance Movement |

| Wovoka's

"Messiah Letter" (—by the Paiute founder of the Ghost Dance movement) |

| 1973: Wounded Knee Occupation |

71-day stand-off between federal authorities and A.I.M. (the American Indian Movement), led by Dennis

Banks & Russell Means; demands: recognition of treaties, etc. (failed); death of two FBI agents led to arrest

of Leonard Peltier—deemed by Amnesty International as a "political prisoner" |

TH, Jan. 25th:: TH, Jan. 25th::

.jpg) |

"Grandma's Photo" |

|---|

| Regarding questions of Native identity and Western patriarchy, my grandmother's photo (from 1943; click photo for larger version) is instructive.

It is ostensibly authentic, at first glance: this is my little Mnikoju Lakota ("Cheyenne River Sioux") Granny, after all.

On second glance, however, the fact that Grandma is wearing a traditional male Lakota headdress is entirely inauthentic—and just totally culturally inappropriate;

it can easily be read as an imposition of the (Western) patriarchy.

Note that the image is very much situated in a moment of U.S. history and ideology; Grandma's 1943 public display was for a Lewis & Clark celebration largely spurred by World

War II American patriotism: "Hey, let's get some local Injuns all dressed up in full regalia, too!"—as further "moral support" (and with perhaps the implicit understanding that

these "defeated people" are fine reminders of the U.S. military's might). And again, the fact they had her "crossdress" (as it were) as a male chief is symptomatic of a patriarchal culture & worldview.

|

| Paula Gunn Allen [Laguna Pueblo]: Introduction from The Sacred Hoop (1986; 1992) [pdf] |

|---|

| | * Origin of Sacred Hoop title/motif: via her mom, and Black Elk Speaks, Allen learns that "animals, insects, and plants" deserve the "respect" given to humans, that life is a "circle," a "sacred hoop" (1). . . . . later: "the complementary nature of all life forms" (3) |

| | * Allen's 7 "major themes" of Native American Lit.: |

| | | 1) "Indians and spirits are always[?!] found together" (2). [Later:] "the inevitable presence of meaningful concourse with supernatural beings" (3) |

| | | 2) SURVIVAL (cf. Harjo & Bird Intro): "Indians endure" (2). |

| | | 3) "Traditional tribal" cultures were "gynocratic," "never patriarchal"; moreover, such a "gynocratic" view—based "on ritual, spirit-centered, woman-focused"—is in line with, and fine support for, current "activist movements" (2). . . . . "the centrality of powerful women" (3) . . . . Definition of "gynocracies": "woman-centered tribal societies" (3)—including "female deities of the magnitude of the Christian God" (4) |

| | | 4) The genocide of Native Americans by Western colonization stems largely from the latter's patriarchal fear of the former's matriarchal basis: thus an attempt at cultural erasure "to ensure that no American and few Native Americans would remember that gynocracy was the primary social order of Indian America prior to 1800" (3). [Note: my—uh—reservations regarding Allen's anthropological theories were expressed in class. Allen herself later admits that various tribes are "as diverse as Paris and Peking" (6).] |

| | | 5) "There is such a thing as American Indian Lit"[!]—and a nice [Western academic!] breakdown thereof: a) traditional lit.: i) ceremonial [sacred] and ii) "popular" [non-sacred]; b) contemporary lit, incl. many Western genres, plus an emphasis on "autobiography, as-told-to narrative, and mixed genre works"—but still incorporating "elements from the oral tradition" (4). [Notes: Allen's "main"(?!) reason for studying NA lit—'cuz it helps us understand Anglo-American writers?! (4)—seems rather peripheral; 2ndly, her conception of "American Indian literature" as a unified "body," a "dynamic, vital whole" (4) smacks of a pan-Indian essentialism that this Lakota resents!] |

| | | 6) Western interpretations of NA culture inevitably "erroneous" (4), based as they are on the bipolar (+/-) stereotypes of the "noble savage"—that "guardian of the wilds and . . . . conscience of ecological responsibility"!—and the "howling" or "hostile savage"—the stereotypical image "most deeply embedded in the American unconscious" (4-5) |

| | | 7) Native American cultures based on "sacred, ritual ways" are similar to many (heck, most) other non-Western cultures of the world—partaking, indeed, in a "worldwide culture that predates western systems derived from the 'civilization' model" (5; what deep ecologists Devall & Sessions have dubbed the "perennial philosophy"); thus NA people have shared with those of the Third World the "outrages of patriarchal industrial conquest and genocide" (6). |

| | * Allen's personal-autobiographical finale: her ideas originate from a "Laguna Indian woman's perspective . . . . unfiltered[?!] through the minds of western patriarchal colonizers" (6; and yet several of her later notions derive specifically from the European psychology of Carl Jung!). |

| | | —Like Leslie Silko, she identifies with the Laguna Pueblo goddess, Yellow Woman: she is "'Kochinnenako in Academe'" (6). |

| | | —Native-identity assertion: Allen's "self who knows what is true of American Indians because it is one"; however, note that this turning inward towards an individual "inner self" is itself a quite Western-Civ. enterprise (6). |

| | | —But she is both Native and Western-Civ., at last? ("somewhat western and somewhat Indian")—both reflective & observational (Western), but also "metaphysical," evidenced in her "guidance from the nonphysicals and the supernaturals"—including the "Grandmothers"; and so her "New Age-y" coda, in which she thanks the elements of nature, the "sticks and the stars" for the best "training" that she has garnered (7). |

| Joy Harjo [Muscogee] &

Gloria Bird [Spokane]: Introduction to Reinventing the Enemy's Language (19-31) |

|---|

| Main—er, "crucial"—threads (or weaves, or lines of beadwork, etc.!): |

| * Female (& Native) "kitchen-table" domesticity/conviviality: 19, 20, 21, 22 ("beadwork" metaphor) |

| —Intimacy/personalism: 19, 21, 28 |

| * Emphasis on collaboration, on the "collective," communal, dialogic: 19, 21, 23, 31 |

| —"This collection" = "the collective voice of nations" (31). |

| * Problem: Native oral tradition vs. Western written tradition: 20, 28 |

| —English as language of colonization/repression: 20, 22, 23, 24 . . . . incl. the publishing industry: 22 ("Often, the voice of tribal, land-based women writers with ties to community, history, and language has been marginalized and silenced by those who control what is published" [22].) |

| —Solution: "reinventing the enemy's language"/"decolonization" via Native writing: 21-22, 23-24, 25-26 . . . . "Many of us [Native women] at the end of the century are using the 'enemy language' with which to tell our truths, to sing, to remember ourselves during these troubled times. . . . . [T]o speak, at whatever the cost, is to become empowered" (21) . . . . . "We've transformed these enemy languages. . . . . [We are] 'Reinventing' in the colonizer's tongue and turning those images around to mirror an image of the colonized to the colonizers as a process of decolonization" (22). |

| * Diversity (both tribes and genres): 23, 21 . . . . incl. Canadian Natives & Latinas: 27 |

| * SURVIVAL: 24, 25-26, 30, 31 . . . . and the necessity to be political: "That we are still here as native women in itself is a political statement. . . . . The stories and songs are subversive" (30). |

| * Native worldview: "ways of perceiving" (24), "new paradigms" (29) |

| * "Borders": 26 |

| * Identity (Native & female): 26-27 |

| —Problem of tribal identification: 26-27 |

| * Structure of the anthology: "(1) genesis, (2) struggle, (3) transformation, and (4) the returning" (29) [Question: whose (Euro-)theory does this remind you of?! (Campbell's "hero's journey," etc.] |

| * [most explicit] feminist statements (and partial support for PGA's argument regarding the centrality of women in pre-contact Native America): 30 |

| * Finally: "The literature of the aboriginal people of North America defines America. It is not exotic" (31). |

| * OOPS—a literary "typo": it's not "Henry Wordsworth Longfellow" (25); GB is confusing William Wordsworth with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. (But maybe this is a "reinvention"?! ;-}) |

An EXTRA CREDIT opportunity:

• Paul A. Olson Great Plains Lecture: Amy Lonetree: "Decolonizing Museums and Memorials: Reclaiming Narratives and Centering Indigenous Survivance"

WHERE & WHEN: Center for Great Plains Studies, Jan. 25th, 5:30

—"Indigenous communities have long called for more rigorous interpretation in museums and historic sites that gives voice to the Native American experience and honors their survivance. In her talk, Amy Lonetree (Ho-Chunk Nation) will consider the ongoing project of decolonizing and Indigenizing museums, lessons learned, and the challenges of reclaiming Indigenous ancestors and cultural belongings in colonial institutions. Lonetree will also explore the importance of unsettling colonial representations on the memorial landscape and the need to center Native voice and perspective in interpretation in museums and memorials."

Extra credit—10 points (possible, not automatic): a written summary/response of two-or-more double-spaced pages; emailed to me by M, Jan. 29th, midnight

|

TU, Jan. 30th:: TU, Jan. 30th::

| June McGlashan [Aleut]: "The Island of Women" (67-71) [poem] |

|---|

| | * Biog. intro—NOTE: Mary TallMountain = well-known Athabascan (Alaskan tribal) poet. . . . |

| | * Example of PGAllen's "gynocracy"?!: in the Aleut tribe, "a woman can be a shaman" (68); story of the "ambitious young woman" who forms "a group of hunters" (69), and saves the tribe via a sea-cow [a sexist name, that!?] hunt (69-70). . . . (BTW, Steller's Sea-Cow, a manatee-like mammal, would be extinct by 1768, soon after its discovery by Arctic explorers.) |

| | * But the untoward & curious finale: marriages with Russians, even given the penultimate stanza in which marriage and "civilization" are equated to rape & murder (71)? . . . |

| | * But SURVIVAL again, in the final stanza—via "the children" (71). . . . |

| Janice Gould [Maidu (N. Calif.)]: "Coyotismo" (52-53) [poem] |

|---|

| | * Our first exposure to an incarnation of the native Trickster archetype, a "mythic" figure who fosters tribal survival via humor & cultural renewal (often via an apparently impulsive destruction of the "old"). . . . |

| | * "Coyote" is one of the most common incarnations of the Trickster; here the narrator is a literal "archaic" coyote in the first 2 stanzas (52); then she merges into the contemporary human, a "poor" and "hungry" Indian girl, who performs Trickster-esque manoeuvres in the present day (52-53). |

| | * Note, too, the specifically female associations with the moon, her "sex," and the final stanza that reads like a paragraph from Cixous' "Laugh of the Medusa," with its tone of uncontainability, its relish of "All things insatiable" (53). |

Note on the TRICKSTER archetype/NatAmer deity-motif (see, for instance, Alexie's "Crow Testament," above): In NatAmer folklore/myth in general, Coyote is the most

common Trickster, a cosmic & natural force blessed with both sheer animal "stupidity" and uncanny animal cunning. In Lakota stories,

for instance, he is forever losing his tail, getting chopped up into bits, and generally making a mess of the cosmic order.

But he always comes back to life, and the world is better off for his shenanigans. (Also prominent as a Trickster

in Lakota myth is Iktomi, the spider. In the Pacific Northwest, Raven [or Crow, or even Blue Jay] is Trickster.) The function of these

tricksters has long been debated. My own reading

relies on Jungian psychology, Bakhtinian dialogism, and ecology/ecocriticism. Jung reads the trickster as an aspect

of the Shadow archetype—that "dark" complex of the unconscious psyche whose real role is to make the ego

realize that it is out of balance, through its sheer repression of that "dark" side. The literary theorist

Bakhtin claimed that the dominant social discourse towards order and reason necessarily entails a "polyphonic"

(multi-voiced) reaction, in myth, literature, and society itself. Regarding this latter, he points to various

cultural manifestations of "Carnival," wherein the common folk go "crazy" in an established ritual that is

directed against the (repressive) social order. (Cf. Mardi Gras!) Finally, in a purely naturalist/ecological sense,

the Trickster is "raw" instinctual animal, always erupting into "civilized" (and repressed) human consciousness

as a magical & numinous force—again, as a corrective against an oh-so-blind ego-faith in order and rationalism:

a reminder at last that WE are animals, that cosmic evolution needs entropy and chaos, that to remain in any blithe

condition of stasis is a psychological and cultural death.

Note on the TRICKSTER archetype/NatAmer deity-motif (see, for instance, Alexie's "Crow Testament," above): In NatAmer folklore/myth in general, Coyote is the most

common Trickster, a cosmic & natural force blessed with both sheer animal "stupidity" and uncanny animal cunning. In Lakota stories,

for instance, he is forever losing his tail, getting chopped up into bits, and generally making a mess of the cosmic order.

But he always comes back to life, and the world is better off for his shenanigans. (Also prominent as a Trickster

in Lakota myth is Iktomi, the spider. In the Pacific Northwest, Raven [or Crow, or even Blue Jay] is Trickster.) The function of these

tricksters has long been debated. My own reading

relies on Jungian psychology, Bakhtinian dialogism, and ecology/ecocriticism. Jung reads the trickster as an aspect

of the Shadow archetype—that "dark" complex of the unconscious psyche whose real role is to make the ego

realize that it is out of balance, through its sheer repression of that "dark" side. The literary theorist

Bakhtin claimed that the dominant social discourse towards order and reason necessarily entails a "polyphonic"

(multi-voiced) reaction, in myth, literature, and society itself. Regarding this latter, he points to various

cultural manifestations of "Carnival," wherein the common folk go "crazy" in an established ritual that is

directed against the (repressive) social order. (Cf. Mardi Gras!) Finally, in a purely naturalist/ecological sense,

the Trickster is "raw" instinctual animal, always erupting into "civilized" (and repressed) human consciousness

as a magical & numinous force—again, as a corrective against an oh-so-blind ego-faith in order and rationalism:

a reminder at last that WE are animals, that cosmic evolution needs entropy and chaos, that to remain in any blithe

condition of stasis is a psychological and cultural death.

|

| Roberta Hill (Whiteman) [Oneida (Wisconsin)]: "To Rose" (309-310) [poem] |

|---|

| | —A poem to her "sister," now separated from her—why? (See 1st sentence and last sentence on p. 310.) |

| | —Nice image of rain turning to snow: "the rain . . . fell twinkling" (309)! |

| | —Effective "pathetic fallacy" poeticisms in the last stanza: "the land here / won't wake without you, Rose"—as all of nature's beings (& places) seem dead without her (310). [Pathetic fallacy: projecting human emotions upon the non-human (often non-human "Nature"); closely related to personification. BTW, Leslie Silko has pointed out that this definition assumes, of course, the Euro-/Western notion that inanimate (or "dumb animal") Nature is dead (or stupidly unconscious).] |

| | —Key questions: why does the narrator think that her sister should "Come home"? How is this related to her sister's "heart" (top of p. 310 and final line)? |

| Luci Tapahonso [Diné]: "What Danger We Court" (315-316) [poem] |

|---|

| | —autobiogr. intro: Tapahonso's notes on the Navajo (Diné) language worthy of note |

| | —Another "sister," this one "courting danger" at "the only stop sign for miles around" (315)! |

| | —As in the Tapahonso short story we'll read later, a great regard for family, especially children: "Your children cry and cry to see you . . . your voice gathers them in" (316). |

| | —Another refrain of survival, at last—"It is the thin border of a miracle, sister, that you live . . . [and finally:] sister, we have so much faith" (316)—but here that "faith" seems directed more generally—at all women? or all humankind? |

| Marla Big Boy [Lakota/Cheyenne (Northern ~: Montana]: "I Will Bring You Twin Grays" (317-319) [poem] |

|---|

| | —A poem, as she tells us in the intro, about "pre-contact time," when "[i]ntertribal war was common" (317); thus the digs at the "no-good Osages," who would "slit a Sioux's throat just / to show they are better than us" (318). Then there's the historical reality that the captives of such warfare were as good as slaves, fit for barter & trade. |

| | —The narrator's promise to her captive sister (and cool simile): "An orange sunrise recaptured the stars like / I'm going to recapture you, my sister" (318). |

| | —Great line?: "Gentle singing brings tears to his tired eyes" (318). |

| | —They learn of the sister's specific Osage captor (318); and so plans are made for lots of bartering(!), at last to trade(?!) two horses—"Twin Grays as fast as lightning"—"to bring you home / My sister" (319). |

TH, Feb. 1st:: TH, Feb. 1st::

| Elizabeth Woody [Diné/Warm Springs Wasco]: "The Girlfriends" (102-104) [poem] |

|---|

| | * Two old women, the narrator and her more "fertile" friend, who are contrasted via a series of (at first quite vague) metaphors. . . . |

| | * But Woody's Diné background—corn!—helps clarify the poem's meaning: the narrator's "empty husks" are contrasted with the other's "pollen, fertility," until it becomes clear by poem's end that the latter has been blessed with children, the former (only) by oratory, the gift of language; both, the poem intimates, are means of survival? |

| Gail Tremblay [Onondaga/Micmac (New England/E. Canada)]: "Indian Singing in 20th-Century America" (169-171) [poem] |

|---|

| | * Title poem of her 1992 collection of poems |

| | * "Theme": the contemporary Native plight of living in "two worlds" (170): |

| | | 1) a Native world of naturism (the here-and-now as "spiritual")—of "light" and "breath," of everything "singing" & "dancing" (incl. stones and trees!) (170)—at last, a "singing round dance" of life "impossible to ignore" (171) |

| | | 2) an Anglo world of "patterns of wires invented by strangers" (170), which would "shut / out magic" (171) |

| | * In this two-world schism, Natives are "inevitable as seasons[!] in one, / exotic curiosities in the other"; and the language problem: "we wonder / whether anyone will ever hear / our own names for the things / we do" (170).

|

| Alice Lee [Métis (Canadian mixed-blood)/Plains Cree]: "Confession" (186-187) [poem] |

|---|

| | * (This poem—serpent metaphors and all—is too starkly self-evident for me to add anything.) |

| Lois Red Elk [Dakota]: "For Thieves Only" (187-189) [poem] |

|---|

| | * Biog. intro: maka = earth; unche = grandmother (187); pronounced "MahKHAH oonCHAY" [Lakota: unci maka (oonCHEE...)] . . . Note also, in contrast to the Diné's close ritual connection to corn, the Dakota (& Lakota) are "horse people" (188). |

| | * The poem an alternating of positive/negative polarities, with the insipidly positive "Indian Princess" refrain offset by intentionally more "sinister" verses, in which the poet rehearses, and rhetorically embraces, such negative stereotypes as "redskin" (188) and "heathen soul" (189). Whatever the stereotypes, "I have survived" and am ready for the "thieves," whom she addresses in the final stanza. What does she mean, then, by the final declaration, "I'll show you what you never learned" (189)? |

| | * (In some ways, especially its tone, Red Elk's poem really seems to be an inferior imitation of Diane Burns' "Sure You Can Ask Me a Personal Question"?!) |

Nora Marks Dauenhauer [Tlingit (pronounced KLINK-it) (Alaska)]: "How to Make Good Baked Salmon from the River"

(201-206) [poem] |

|---|

| | * Note: Dauenhauer is well-known as the foremost Tlingit linguist/translator, doing more than anyone to preserve her first language. |

| | * "How to Make . . ." is from her 1988 collection The Droning Shaman Poems. |

| | * (In terms of Western aesthetics, the best poem we've read so far?! Though Midge's "Written in Blood" [below] is right up there, too.) |

| | **** Poem = "recipe"!—note the main ironic/humorous tone, as each item of the traditional recipe is adapted to contemporary (and economic) needs, via the refrain "In this case." (Another common Native "theme": survival = adaptation!) |

| | * Retained is the traditional regard for other species as equals: the "seagulls" and ravens (203); mosquitoes & ravens (205); and the salmon (206). [Note: for many tribes of the Pacific Northwest & Alaska, Raven is the main Trickster figure, which clarifies the "crack" about the bird on 205.] |

|

|---|

|

Something close to this almost happened after Custer's massacre of Black Kettle's Cheyenne band at the Washita (see Custer's My Life on the Plains).

|

TU, Feb. 6th:: TU, Feb. 6th::

| Chrystos [Menominee (Wisconsin)]: "The Old Indian Granny" (231-233) [poem] |

|---|

| | * From her 1995 collection Fugitive Colors |

| | * Biog. intro: interesting stuff—fan of the Beat poets, & existentialism (231-232) . . . at one time, "on the streets and in and out of nuthouses" . . . now a "political" activist for "First Nation people." |

| | * Plath-like confessionalism: "on my way to therapy" (and the humor[?!] of "how much I owe my therapist / who is saving my life") (232) |

| | * Or is it the "Indian Granny" who is her real therapist?—who "travels with me her sweet round brown face / appears in my dreams" (232)? |

| | * But the old woman has succumbed to drink, perhaps "to kill the pain of this graveyard they've made / this new world where her only place / is crouched on cement" (232). |

| | * The narrator was once into drugs, too—"to tie off the ache" (233). |

| | * Then she addresses her therapist, who's told her "about all the Indian women you counsel"—victims of sexual abuse, violence, and self-loathing—"who say they don't want to be Indian anymore" (233) . . . and her?—"Sometimes I don't want to be an Indian either"—but she must suppress such thoughts now because she's "so proud & political." |

| | * Still, she has "no home to offer a Granny" . . . and the final dire thought "that if you don't make something pretty / they can hang on their walls or wear around their necks / you might as well be dead" (233). |

| Dian Million [Athabascan (Alaska)]: "The Housing Poem" (PDF on Canvas) |

|---|

| | * Biog. intro another lament about forced adoptions, the "whole history of the attempt to destroy our families" (Harjo & Bird 163-164) |

| | * Semi-humorous, semi-poignant, poem of an extended family (Lakota: tios[h]paye) that gets larger and larger, and happier—until the landlord wants to evict them, with the final play on the meaning of "single-family occupancy" (Harjo & Bird 166) as revelatory of cultural differences/misunderstandings . . . |

| Mary Brave Bird [Lakota]: "We AIM Not to Please" (336-352) [essay/chapter excerpt] |

|---|

| | —from Lakota Woman (1990; as Mary Crow Dog [wife of Leonard ~!]; with Richard Erdoes) |

| [PART I: A.I.M. in general, & its origins:] | (see next "table" for timeline) |

|---|

| | —B.B.'s several comparisons of the excitement of A.I.M. with the 1890 "Ghost Dance fever" (337, 345, 346, 350) . . . The Lakota song (337) is translated immediately below ("Maka" = earth, or here, world; "Oyate" = the people, translated here as nation; etc.) |

| | —B.B.'s several acknowledgements of A.I.M.'s limitations & failures (337-338; 339; 343 [and defense!]: "Aside from ripping off a few trading posts, we were not really bad" (344)!? |

| | —A.I.M.'s sheer controversial novelty (don't I remember!—as a high school student in SoDak at the time): "Some people loved AIM, some hated it, but nobody ignored it" (338). |

| | —Leonard Crow Dog (338, etc.): young & charismatic Lakota medicine man, one of the 1st Lakota (& "holy men") to give A.I.M. some legitimacy in Pine Ridge (SD). (What Brave Bird downplays is how many of the "apples" on the Rez (see note on the "lost generation," below) were against A.I.M. My mother, for instance, commuted to Pine Ridge from Rapid City for her job at this time—c. 1973—and told me that she felt terrified.) |

| | —A.I.M.'s origins among urban "ghetto Indians" in Minneapolis/St. Paul—who discover on the Pine Ridge Rez some sense of tradition & ceremony (339; a gesture that other Native scholars have viewed more critically, as a "wanna-be" mentality/motive of questionable authenticity) . . . ergo the re-emphasis on the traditional Sun Dance ceremony (342) . . . Many "came from tribes which had never practiced this ritual. I felt it was their way of saying, 'I am an Indian again'" (345). |

| | —Radical-protest rhetoric borrowed in part from the black Civil Rights movement; but note B.B.'s distinction between what each minority race wants (340), a point already made by Vine Deloria in Custer Died for Your Sins. |

| | —Government-forced sterilization of Native women (341-342; cf. Harjo's essay); why?: "there were already too many little red bastards for the taxpayers to take care of" (341). |

| | —Protests: against anthropological digs; "Indian political trials"; "NO INDIANS ALLOWED" signs (342)! |

| | —Interesting commentary on the coalition of the young AIMsters and the traditional elders, while those in the middle were a "lost generation" of despair & govt. handouts (342) |

| | —B.B.'s pride in the Lakotas' seminal role in A.I.M. (342-343, 345); yet a concomitant knowledge that this is rather against the pan-Indian emphasis of A.I.M., its call for "tribal unity" (345; see also 352). |

| | —WOMEN's role in A.I.M. (343, etc.): "'A nation is not dead until the hearts of its women are on the ground'" (343—something Custer, et al., nearly managed!?). |

| | —Local white reaction to A.I.M. in Pine Ridge (343-344; again, I remember): Black Hills tourist traps—you're "scaring the tourists away" (343)! minority-rights lawyer Kunstler: "'You hate those most whom you have injured most'" (343-344). |

| | —B.B.'s retrospective evaluation of the movement: "I don't know whether it will live or die"—but "one can't take away from AIM that it fulfilled its function and did what had to be done at a time which was decisive in the development of Indian America" (344-345). |

| [PART II: the Trail of Broken Treaties:] | |

|---|

| | —the Trail of Broken Treaties = "the greatest action taken by the Indians since the battle of the Little Bighorn [1876]." Fittingly, the Cherokee followed the Trail of Tears; the Lakota started out from Wounded Knee (346). |

| | —Initial poor living conditions (another "broken promise") (347)—so the "unplanned" occupation of the B.I.A. building (347-); peaceful protest had not worked: "We were not wanted" (by the Nixon administration, et al.); Dennis Banks: will it take "another Watts" to be heard?; the drawing up of "twenty Indian demands"—"all rejected" (349); the chaotic (& semi-humorous) state of "siege" (350-) . . . Oh, but the TOURISTS once again!: taking "snapshots," and "hoping for some sort of Buffalo Bill Wild West show" (351). |

| | —Women encore (besides B.B.'s own foray "downstairs" [350]): Martha Grass, the "simple[?!] middle-aged Cherokee woman" who stands up to the Interior Secretary, talking "about everyday things, women's things, children's problems"—and them flips him the bird (351-352). |

| | —Coda/retrospective: "Of course, our twenty points were never gone into afterward . . . . But morally it had been a great victory. We had faced America collectively, not as individual tribes" (352). |

** A.I.M/"Red Power" Timeline:

* 1968: founding of A.I.M. (the American Indian Movement) (in MN); original leaders included Dennis Banks, the Bellecourt brothers (all Anishinaabe ["Ojibway" or "Chippewa," as Brave Bird calls them]) and Russell Means (Lakota); but, according to Brave Bird, "it was an Indian woman who gave it its name" (339)!

* 1969: occupation of Alcatraz (CA)

* 1972: Trail of Broken Treaties march (to Washington, D.C.); the main treaty they had in mind was the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which guaranteed the

"Sioux" the Black Hills, a promise soon broken by Custer & gold-lust. . . . Here is the TRAIL OF BROKEN TREATIES 20-POINT POSITION PAPER.

* 1973: Wounded Knee Occupation—The Legacy of Wounded Knee (thorough set of articles on AIM's 1973 insurrection [Sioux Falls Argus Leader]).

|

| —Works Cited entry for today's video:

Wounded Knee. Dir. Stanley Nelson. Part 5 of We Shall Remain. American Experience/WGBH International, 2009. DVD.

(I played 17:28-31:45, on the general history of A.I.M.)

|

|---|

TH, Feb. 8th:: TH, Feb. 8th::

| Lee Maracle [Salish (Pacific Northwest)/Métis (Canadian mixed-blood)]: "Who's Political Here?" (246-258) [short story (fiction)] |

|---|

| | * From her 1990 collection Sojourner's Truth and Other Stories |

| | * Very humorous fiction about a narrator deftly handling the overwhelming chores of motherhood, versus her "political" (and whining) husband & friends (cf. the title) . . . |

| | * Husband Tom (247-249): helpless as a child without any clean underwear!—but going downtown to "poster" (i.e., with radical political pamphlets/flyers) |

| | * Arduous trip, with buggy + 2 kids, to Safeway, where she meets Tom's friend, Frankie—a womanizer (249-251) . . . great slam at the sexism & machismo of John Wayne movies (251) |

| | * Then, back home, the narrator, who has never made a close connection between "Sex, love, and morals," has a roll in the hay with Frankie (251); in contrast to the narrator, Frankie is riddled with guilt throughout the rest of the story. |

| | * News from friends: Tom's in jail (251-252)—bail him out!? The narrator: look at MY travails; look at the politics of everyday human life that I have to juggle: "Who is in prison here?" |

| | * Frankie attacks her mothering skills regarding her daughters: "'they're wild'" (254); "'This is a gawdamn zoo'" (255). |

| | * "More of Tom's friends" show up, whose grandiose political pretensions are laughable (256). One is Patti, with whom Tom is having an affair. The narrator cares little about that (256-257); what bothers her is that Patty is respected by the men for "her brain": "I'm jealous of Patti, not sexually, but because my husband and her friends accord her her mind" (257). |

| | * After the strange "politics" of her day, the narrator gives free rein to "Rolling, changing emotions" (257)—including "Panic," until she imagines her "old granny's face" grinning "through the wall." This vision is a calming influence, since the old woman seems to have been saying, "Let it roll, let it rage," this "storm" of emotions. Now they become "exhilarating," and lead to the story's epiphany (and rebuttal to Frankie's crack about her kids): "yes, they are wild. Wild, untamed, unconquerable, and I was going to go on making sure they stayed that way" (258). |

| Winona LaDuke [Anishinaabe (i.e., Ojibwe) (Minn./Wisc./Mich.)]: "Ogitchida Ikwewag: The Women's Warrior Society, Fall 1993" (263-269) [short story (fiction)] |

|---|

| | * Biog. intro: note, of course, LaDuke's emphasis on "social activism." |

| | * Opening Native/New-Age cleansing ritual, in a "Circle," under the "full moon" (264-265) |

| | * The problem: sexual abuse, of 11-yr.-old Frances Graves, by her father Fred Graves, powerful tribal councilman (265-266) . . . the sad fact that this is hardly an isolated case in the community (266) . . . |

| | * Righteous retribution: the "Circle" of "Warrior Society Women" wait outside Grave's house—with "ricing sticks" (266; any ironies/metaphors here?)—catch him in the act, cane him unmercifully, lead him outside "naked to the waist down," to public shame and spectacle (266-269). |

| | * [Later ADD:] LaDuke would soon revise this short story into a chapter in her novel Last Standing Woman (1997). |

| Anita Endrezze [Yaqui (Mexico/Arizona)]: "The Constellation of Angels" (281-288) [short story (fiction)] |

|---|

| | —intro biog.: note her love for painting (281)—and then the many colors and "paintings" in the story that follows. (Similarly, I told you that I knew her better as a poet—also evident in her poetic prose tour-de-force here.) |

| | —"Poetic" opening, with such phrases as "aching like an orchid" (282) . . . |

| | —Narrator: some ethereal being, from "the temple of the dream-walkers"—and the reader goes, "huh?"; until we learn of Mary—"my Other: my special human" (282), and we realize (eventually) that the speaker is some Native/New Age "guardian angel" . . . |

| | —Mary, in contrast, "lives in the dark cracks of the city," is pregnant "with a new human hungry for wholeness" (note the alliteration)—and "her man" beats her (282). . . A bad relationship: he "has big heavy boots that do not always care about what they step on," while she is too passive, in her "self-effacing camouflage"—an enabler, at last (282). Furthermore, he is cheating on her, in part because the other woman "is different from Mary, whose belly was baglike" (more alliteration) (283). |

| | —"His" further (& poetic) characterization: "His thoughts are like an onion made of ash: no center"; and "his soul: it has a rind on it, thick and knotted." . . . For the other "young men" of the urban neighborhood, too, "Something is broken. It is Life" (284). . . . Versus the "marvelous" tree imagery associated with Mary (see next)—"his ears feel like there's a big tree growing in each of them, the roots digging into his brain" (285)! |

| | —In contrast, Mary "sings her thoughts," thinking sometimes: "'I should only love a tree, with its owl eyes, its blue feathers, its crow voice"! . . . She also doesn't drink, smoke, or use drugs; her only fault: "But she does need him" (284). . . . Ergo the "contradiction" in her character: "a vast difference between the Mary of the trees with the wooden hearts [and owl eyes] and the Mary of apologies" (285). . . . |

| | —Return to the initial other-worldly setting & atmosphere, "the temple," where "music has eyelids and breasts are made of sunlight[!]" (in these sections, her "poetry" makes abundant use of surrealism and synaesthesia). . . . "we dance further than trees can see" (285). |

| | —The PLOT: our narrator meets "another dream-walker," in charge of Mary's unborn, who knows the baby's untimely fate; Mary has a "terrible pain"—a miscarriage—and a resulting change of style, a rather James-Joycean poetics, to represent pre- (or post-?) human consciousness. . . . |

| | —The baby's death = trip (return?) to "a constellation of angels" (286-287). Why is the baby referred to as "O White Shell clan woman!"? . . . Death, oh—"when the jar falls it breaks / and her soul falls out" (286); "little baby-woman: her soul has burned a spirit hole / into the temple of the sky"; alliteration!: "here is the altar of innocent eyes"; and a God-the-Mother, apparently, "the starry mother who is strong enough / to keep you whole" (287). . . . At last in "the temple, the Flower World"; note how the four directions are implicit in the descriptions of the third-to-last paragraph (288). |

| | —But then, "this" world, and Mary's plight; worst, perhaps, the clerk's words, "'Don't they know they shouldn't drink when they're pregnant?'" Or worse yet, the reality: "'Looks like she was all beat up'" (287). . . . Out-of-body experience, in which the "baby floated up and looked down at her mother" (287-288); last paragraph: "In the other world," Mary is loaded "into the ambulance." What do you make of the last phrase, "the sweet smell of blood flowering between her thighs" (288)? |

RESPONSE #1 (2 pages or more)—60 points—Due TU, 2/13, midnight (uploaded to CANVAS as WORD doc)—CHOOSE ONE (and please specify which): RESPONSE #1 (2 pages or more)—60 points—Due TU, 2/13, midnight (uploaded to CANVAS as WORD doc)—CHOOSE ONE (and please specify which):

a) Write your own focused personal/autobiographical narrative that explores a "theme" (or themes) evident in our readings so far (identity ["race"/ethnicity and/or gender and/or . . .]/generations/"returning home," etc.), relating your life experience to "a goodly number" of our readings to date (from the PGA essay to the Power short story).

b) Compare/contrast the two intros (Allen vs. Harjo & Bird), considering especially Allen's notion of "gynocracy" vs. Harjo & Bird's calls for "reinvention" & "decolonization": which intro do you find more cogent, less inflammatory & "out there"? (You might also consider differences in tone & style.) . . . Finally, you should also point to "a goodly number" of our later readings (thru Power) as evidence that one or the other intro is more "right on" in terms of Native women's writing.

c) Of the various poems read to date (thru Dauenhauer's "How to" poem), rank your "Top 5," and explain the reasons (based, of course, on valid criteria!) for your ranking.

d) Ask ChatGPT to write a one-paragraph "analysis" of one of the texts in this range of readings. Then write your own paragraph that point outs how stupid, wrong, and/or insufficent the ChatGPT analysis is. (Yes, cut & paste the ChatGPT paragraph into your response.) REPEAT this process for two other eligible texts. (Problem: ChatGPT won't be able to do anything with texts not available online [except perhaps create some truly stupid gibberish?], though you could type in an entire poem for it, etc. But be "ethically" aware that this does give its AI engine even greater power, down the line, to CHEAT for other students!)

e) Finally, as announced on the syllabus and in class, a do-your-own-thing/anything-you-want "reader's journal" that addresses "a goodly number" of our assigned readings is an alternate to the specific prompts above; but again, be as "comprehensive" as possible, and avoid simple plot summaries or a simply rehashing of ideas brought up in class or on the course web notes. (Feel free to object to/expand upon these, of course.) [This last caveat applies to all response choices.]

Final Note: As indicated on the syllabus, ONE MAIN grading criterion is how well you demonstrate that you've been doing the readings. In this regard, option e may well be your best choice, especially if none of the previous options rings a bell for you. Note that you can still begin that "reader's journal" right now—just go back to the beginning of the syllabus, and offer your own analytical or creative commentary/responses to a good number of the readings to date (without simply repeating what was said in class). In sum, one option, then, is—"free response."

|

Another EXTRA CREDIT opportunity:

• Paul A. Olson Great Plains Lecture: Patricia Norby: "Native American Art at The Met[ropolitan Museum of Art]"

WHERE & WHEN: Great Plains Art Museum, Feb. 12th, 5:30

—"Join us for a conversation between Dr. Patricia Marroquin Norby (Purépecha), Associate Curator of Native American Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Margaret Jacobs, Director of the Center for Great Plains Studies. Norby, the first full-time curator of Native art in The Met's 153-year history, will talk with Jacobs about her vital curatorial work that foregrounds Indigenous perspectives and experiences."

Extra credit—10 points (possible, not automatic): a written summary/response of two-or-more double-spaced pages; emailed to me by FR, Feb. 16th, midnight

|

|

|---|

|

—I found this photo online about the time of the 2021 Super Bowl. And the Chiefs are back again. . . . (Yeah, I know, I'm sorry: there are a lot of CHIEFS fans in Nebraska! But sooner or later, people are going to realize that "Chiefs" is damn near as insultingly racist as "Redskins," especially given the arrowhead iconography, and the fans' tomahawk chops & faux-Indian chanting.)

|

TU, Feb. 13th:: TU, Feb. 13th::

| Luci Tapahonso [Diné]: "All the Colors of Sunset" (319-325) [short story (fiction); 1994] |

|---|

| | —1st published in the journal Blue Mesa Review, 1994 |

| | —A wonderfully plaintive story worthy of (& reminiscent of) Leslie Silko's famous short story "Lullaby" |

| | —1st 2 paragraphs: note how well the Desert Southwest setting is given to us, via the 1st-person-grandmother's point of view (319-320). |

| | —Her 5-month-old granddaughter dies: "My first and only grandchild was gone" (320). . . . the deep grief for the dead body, via songs & words & caresses (e.g., the pathos of "'This is called your leg, my baby'"!) (320); though she remembers little, "[t]hey said that I kept the baby for four hours that morning" (321). |

| | —Characteristically, the whole "tribe" shows up to help out (321-322). |

| | —But her subsequent lingering lack of "focus," her feeling "far away from everything"; she's even stopped talking to the animals (322)! . . . Indeed, she prefers to sleep, and to dream, often, of the child, who still seems so near & alive (323). |

| | [—Anything sinister about how/why the baby died?—silence surrounds the cause (323).] |

| | —Her mourning has become inordinate & unhealthy: others see the baby "alive," beside her (323 [including, later, the medicine woman, who tells her "'The baby hasn't left'" (324)]); her sisters beg her to seek help (323-324); so she finally undergoes a near-forgotten healing ceremony: "I could finally let my grandbaby go" (324). |

| | —Finale (& story's "moral"): "I understand now that all of life has ceremonies connected with it" (325). |

| Susan Power [Yanktonai (Nakota)]: "Beaded Souls" (Reinventing 374-392) [short story (fiction)] |

|---|

| | —Autobiog. note: the author is FROM Chicago, i.e., a "relocated" urban Indian (cf. Harjo's "The Woman Hanging" poem). |

| | —Plot & characters, the Cliff Notes version: The Standing Rock "Sioux" narrator, Maxine Bullhead, seems to carry on the family curse by losing her stillborn child and then killing her husband, Marshall Azure, whom she discovers cheating on her with a white woman in the Indian Center in Chicago. The story is framed by her needlework—she's "beading [ceremonial burial] moccasins" for him—in the present tense of the narration (375, 392); however, by story's end, the reader fears for her state of mind, which seems to be approaching that of one of Poe's famous mentally disturbed narrators (e.g., "The Telltale Heart," "The Black Cat"). |

| | —"Anglo heaven" (375): actually, the "Indian heaven" described on the next page (376) is pretty "Anglo" itself!? |

| | —As for the family curse per se, a lieutenant named Henry Bull Head was actually one of the Indian policemen involved in the killing of Sitting Bull, and as in this story, he also died in the skirmish (376-377). . . .

Agent McLaughlin's (pro-Anglo) account of Sitting Bull's death

. . . Of course, the long history of this family curse makes the middle of the story more comedy than tragedy!? |

| | —heyoka {hayOHkha} (377) refers to spirits or medicine men who do things "backwards," in true trickster spirit. |

| | —Sad deal, how the Native valuing of robust & physically strong women—like Maxine—has been corrupted by the fact that "Dakota men had [now] seen too many movies in Bismark [sic]" (379)! |

| | —Yuwipi man {yooWEEpee} (380) is a wicasa wakan (medicine man) who specializes in the yuwipi ceremony, a healing ritual involving sacred stones. |

| | —The wedding, of course, is a veritable hoot, as is the white J.P. himself (380-383). |

| | —In abrupt contrast, the stillborn child is the dramatic low point, or high point of pathos (384-386). |

| | —And so her wish to go to Chicago, to willingly be "relocated" (387-388)—and hopefully renewed, psychologically. But with this wish, the couple immediately begins to have "bedroom trouble" (388; ah, foreshadowing). . . . Once in Chicago, the reality of Relocation sets in, as the Natives are "caught in slum areas," not in the houses on the promising brochures (389). |

| | —Marshall's caught in the act, with a white woman; worse yet/most pathetically: she's "fertile," having had kids who'd "lived" (390)! |

| | —Marshall's final words an almost too obvious thematic protest?: "'We should never have left'" (391). |

| | —wasna {wahSNAH} (390) usually refers to a ball of tallow (beef fat) with other ingredients rolled in—here, chokecherries. |

| | —Besides "Harjo's "Woman Hanging" (also about Relocation in Chicago), this story can be fruitfully compared with Beth Brant's "Stillborn Night," including Maxine's final "vision" of her husband playing w/ her stillborn son (392). |

TH, Feb. 15th:: TH, Feb. 15th::

| Linda Noel [Maidu (N. Calif.)]: "Understanding Each Other" (233-234) [poem] |

|---|

| | * Title ironic, since the man, at least, fails to understand his partner, calling her "'too wild'" (i.e., too Indian?)—for she has a "pagan" high regard for the moon, and the salmon; when these fish are running, she stands by the river "'humming, / all the time believing / fish understand / why you are there'" (234). |

| | * So he leaves her for a bourgeois, presumably Anglo, complacency & propriety, for someone "whose dreams / are laced in perfume / and dishwater suds" (234). |

| Marcie Rendon [Anishinaabe]: "You See This Body" (279-281) [poem] |

|---|

| | —Read the poem aloud, and note how strophe 1 recurs as strophe 9 (280): by its second appearance, has its tone and syllable emphases changed? (Or better: do we finally know how to "read" it?!) |

| | —The identity of the female speaking "I" seems to shift throughout the poem. Who is "she" in ll. 7-8? l. 16? ll. 28, 29? |

| | —How do you reconcile the poem's ostensible "come-on" tone (2nd-person audience includes "leg man"/"ass man") versus the more overtly feminist theme of an eternally surviving (& strong & independent) "Everywoman" (refs. to the "Trail of Tears," "Wounded Knee," Nazi Germany, the Cold War, and Vietnam)? |

| | —Finally, what do you make of the last lines, the "smile" & "eyes" that "turned your head / just long enough"? ("Long enough" for what?) |

|

Its similarities to previous poems we've read by Diane Burns and Lois Red Elk aside, Rendon's "You See This Body" always makes me recall an earlier (1987) and more well-known poem, by African-American poet Lucille Clifton:

homage to my hips

these hips are big hips.

they need space to

move around in.

they don't fit into little

petty places. these hips

are free hips.

they don't like to be held back.

these hips have never been enslaved,

they go where they want to go

they do what they want to do.

these hips are mighty hips.

these hips are magic hips.

i have known them

to put a spell on a man and

spin him like a top!

|

| nila northsun [Fallon Shoshone [Nevada]/Anishinaabe]: "99 things to do before you die" (394-397) [poem] |

|---|

| | —Poem a response to Cosmo's list "of 99 things to do before you die," many of which are "things only rich people could do"; but "what's a poor indian to do," with "no maza-ska"? (395) |

| | —Vocabulary: mazaska (395) [MAH-zah-skah] = Lakota for money (maza = metal; ska = white; ergo, "white metal" = silver); "crow fair" (Crow Fair): famous annual powwow in Montana; "ta-nee-ga" (396) = taniga [tah-NEE-ghah] = Lakota for buffalo stomach/tripe; "skinwalker" (396) = a shape-changing spirit (Diné); "stick game" (396; aka "hand game" or "bone game") = a team guessing game of chance played at powwows, etc. |

| | —And so "a list that's more / culturally relevant" (395): including "20 ways to prepare / commodity canned pork" (396) . . . (Hey, when I was a kid, we only got commodity beef!) |

| | —Including curling "up in bed with a good indian novel / better yet . . . with a good indian novelist" (396) . . . |

| | —Her final "punch line" (and a winking acquiescence to assimilation?!): "not much left undone / though cosmo's / have an affair in paris while / discoing in red leather and sipping champagne / could find a place on my list" (397) |

|

Excerpt from a former student's informal response, which is, in a part, an imitation of northsun's "99 things" poem:

[. . . . . . . .]

so what is a poor student-athlete to do?

come up with a list that is

actually relevant

so my list includes

stay in school

overcome adversity

learn about people who are still overcoming adversity

that started 300 years ago

read about how hard it is to be a native american

no a woman native american

build a house out of stone

convince others that not all of the Indians

were killed by john wayne

trigger my mind's own clicking gun

have more heart than anyone else

curl up in bed with a good joy harjo anthology

better yet

curl up in bed with joy harjo

burn the orchards in the land of big red apples

help the woman on the thirteenth floor

be the yellow horse

who still has faith

[. . . . . . . .]

|

|

|---|

|

—Vis-à-vis our first extra-credit speaker, here's my (old, bad) photo (& meme) of the Lewis & Clark statues—w/ a satirically accommodating Native dude—outside the Great Plains Art Museum.

|

TU, Feb. 20th:: TU, Feb. 20th::

| |  * Louise Erdrich: "The Strange People" (318-320)—

* Louise Erdrich: "The Strange People" (318-320)—

—epigraph: "antelope" as "people" (and Siren-like temptresses)

—initial identification/merger of species: "I am the doe"

—and eerie (cross-species?!) sensuality: "burning / to meet

him"—the "hunt" as sexual attraction!? . . .

—then hunted, killed, and "slung like a sack / in the back of his pickup"—but also still alive, and

"laughing"!

—the hunter prepares to clean her, "thinks to have me" (as both hunter's slain possession & sexually?! [note his "knife"])—but

she is now a "lean gray witch," a female spirit, who escapes, helps herself to his coffee(!), and then crawls back

into her animal "shadowy body" . . . .

—alive, then, again, and the fascinating final line—who is the one she still seeks, this "one who could really wound me"!?

—Finally, consider again my previous comments on how, as ecofeminists tell us, women and animals (and Natives) have

been similarly othered through the centuries. . . .

—AND/OR can the whole poem, the "hunt," best be read as a metaphor/allegory of the human male/female

relationship, including the hunter's sharp(ened) "knife"!? |

| * Erdrich later revised "The Strange People," for her collected poems (Original Fire, 2003), by adding the following ending lines:

Not with weapons, not with a kiss, not with a look.

Not even with his goodness.

If a man was never to lie to me. Never lie me.

I swear I would never leave him.

[full version online] |

| Janet Campbell Hale [Coeur d'Alene/Kootenay (Idaho/Washington)]: "The Only Good Indian" (123-148) [book chapter/essay (nonfiction)] |

|---|

| | * A chapter from her book Bloodlines: Odyssey of a Native Daughter (1993) |

| | * Ultimately the story—by way of her famous great-great-grandfather, John McLoughlin, the "father of Oregon"—of her mixed-blood grandmother, Gram Sullivan, whose life was—uh—more problematic. . . . |

| | * Initial epigraph, by the famous historian Bancroft, who notes that marrying Indian women is a "debasement" of the white race (123; also see quots. on 140)! |

| | * Opening "scene" (124-126)—Hale's childhood visit to the McLoughlin House, now a museum; her great-great grandfather's life/background |

| | * "Good Indian" interpolation: her mother's distinction between "good" and "bad" ones, and Hale's own joke via General Sheridan (see essay's title) (126-127; obviously, being a "good Indian" = assimilation) |

| | * David McLoughlin, John's son & Gram Sullivan's father, who just "rode away" and married a Kootenay woman (127)! |

| | * Gram Sullivan herself, old, grumpy, and paralyzed (127-130), with a mysterious grudge against the author, her granddaughter, because she reminded her "of someone she hates" (128—the central "riddle" that sets us up for the grand coda) |

| | * Maternal aunts' racism, incl. the remark about "an Indian shuffle" (128-129; early profiling!?) |

| | * Present-day Spokane (the city): also racist (130-131); insult word: Siwash—as in "'Stupid Siwash squaw'" (131) |

| | * Mother's self-identity: Irish (132-133) . . . but her pleasant memories of meeting her "exotic" traditional Kootenay relatives (133-134) |

| | * In contrast, Gram Sullivan, who looked Indian, was the outsider, and (perhaps) "felt inferior" (133). |

| | * Grandfather Sullivan's Irish background (134-135), of British "oppression," of later racism in New York City: "NO DOGS OR IRISH ALLOWED" (134; note similar sign in Petersen's essay, against dogs and Indians!) |

| | * Gram's death, and Hale's sudden re-interest in her (135-136): so—research!—especially interesting since the Kootenay were "the only tribe in the region that had been matrilineal, the only one that had had women warriors" (136). . . . First, (more) research regarding John McLoughlin (136-138); and Gram's grandfather, Chief Grizzly (139) . . . then the full pathetic story of Gram's father, David McLoughlin (139-140; 143-145), who "went native" (137): provided with clothes and travel money to attend a ceremony in honor of John M., he is portrayed quite condescendingly in the historical records as a "squaw"-lover (144), and as someone at last who failed to look "presentable"—which Hale realizes is a "euphemism for 'white-looking'" (145). |

| | * General Indian history background: Custer & the Little Bighorn (1876); Carlisle Indian School (140-141; "'Kill the Indian and Save the Man'"!)—and other Indian schools, "notorious hellholes" (141) [including the one I attended in SoDak, Holy Rosary Mission]; the Wounded Knee Massacre (141-142) |

| | * Then Gram's own trip to Spokane, another failure to "look presentable" (145-147) |

| | * CODA: well, then, did Gram "ever hate her Indianness" (147; aka internalized racism)?!—Ah, the rub, and solution to the initial mystery; Hale's own early memory of trying to bleach her skin white with Purex, to get rid of those "hateful brown hands" (147-148); the answer!—ah, this "Indian blood" and "Indian looks"—"Who did I remind Gram of if not herself?" (148). |

Famous photo of slain Mnikoju Lakota chief Big Foot (Si Tanka) at Wounded Knee.

* more Images of Wounded Knee, incl. the open mass-grave trench (or see my meme, below)

|

|---|

—photo "borrowed" from Google Images

(Wounded Knee mass burial)

|

| Bernice Levchuk [Diné]: "Leaving Home for Carlisle Indian School" (175-186) [non-fiction essay] |

|---|

| | * Exposition/narrative framed by her imaginative description of a 19th-c. painting of a boy leaving for Carlisle (176). . . . |

| | * The School itself (Pennsylvania): 1879-1918 (176-177)—reminds her of her own boarding school experience in Arizona (177; me, too! [SoDak]). . . . |

| | * Her present-day visit to the place (177-178): she's directed to the cemetery (178)! |

| | * The "callous" & "brutal" policy & actions of the govt.'s rounding up of Indian students (178-179) . . . |

| | * Carlisle's founding philosophy (Richard Pratt): "The way to civilize an Indian is to get him into civilization" (180; cf. Hale's quot. of more famous version of the motto, "Kill the Indian and Save the Man" [141]); via Christianity and learning a trade. . . . |

| | * Several documentary examples from the National Archives in Washington, D.C. (180-181)—including "Ran 11/25/13" (180)! (Running away is a ubiquitous refrain in Indian boarding school narratives; I did it myself!) |

| | * Learning a trade (181-182)—including tinsmithing: elsewhere, Standing Bear recounts that his tinsmith occupation eventually was useless because, as a student, he had sent so many of his pieces home that no one needed his wares when he finally returned back to his South Dakota rez! |

| | * Levchuk's own (much later, of course) experiences of cruelty in boarding school (182-184)—including rape & molestation (184) . . . |

| | **** Her call to action/awareness: "We must especially remember those who died at Carlisle and never returned home. . . . Cruel and unconscionable policy and practices forever robbed the students of their natural childhood and youth. . . . There must be a healing of all generations of Native Americans who . . . have become stunted and crippled . . . by the boarding school system. The boarding-school experience must be remembered and told in its true reality. . . . Those of us who are scarred . . . should unashamedly tell the whole story of this phase of our Native American holocaust" (185). |

| | * Finale—framing of intro via a return to the painting (185-186): now she adds/imagines the father's words to his departing son, to follow the "good path" (186; note: ts'aa is a Diné ceremonial basket, used here in reference to the boy's bandana "bundle"?). |

TH, Feb. 22nd:: TH, Feb. 22nd::

| Zi[n]tkala-Ša [zee(n)t-KAH-lah SHAH] = "bird-red" (Red Bird) |

|---|

| * TRIBE: "Yankton Sioux" (the Yankton & Yanktonais bands of SE SoDak) = Nakota tribe ([see Dominguez xix (the intro in our edition)], though usually called Dakota, even by Zitkala-Ša herself); blood quantum!: "one half Sioux" (Fisher xix) |

| * LIFE: |

| | 1876: born Gertrude Simmons (her step-father's last name), on the Yankton Reservation (SE SoDak)—the same year, by the way, as the Battle of the Little Bighorn |

| | 1884: missionaries show up; and so to an Indian boarding school—White's Manual Institute—in Indiana (which she attended, with some intervening years at home, to 1895) |

| | [1890: the Massacre of Wounded Knee, about which Zitkala-Ša is oddly "reticent": "Nowhere in these stories is there a reference to this historical act of genocide" (D&N xxxiii).] |

| | 1895-1897: to Earlham's College (Indiana), and to poetry writing & oratory contests |

| | 1897-1899: teaching at Carlisle Indian Industrial School! |

| | 1899-1902?: study at the New England Conservatory of Music (violin) |

| | 1900-1902: composes bulk of her literary output [see next list] |

| | 1902: married to Raymond Bonnin, which some claim signaled the "decline" of her literary career (Fisher xiii) |

| | 1903-1916: living with husband, now a B.I.A. employee, on a Utah reservation. where she further develops her bent for Indian activism—including her . . . |

| | 1913-1918: activist denunciation of Native peyote use, for which the "liberal ethnologist James Mooney . . . denounced" her "as a fraud," for wearing an Indian outfit that was a hodge-podge from different tribes (D&N xxi-xxiii)! |

| | 1916: Bonnins move to Washington, D.C., upon Zitkala-Ša's election as secretary & treasurer of the Society of the American Indian—"the first national pan-Indian political organization run entirely by Native people" (D&N xxix-xv; founded 1911, "dissolved" in 1919); and a new, more public life of activism on behalf of Native Americans, including calling for Indian citizenship (granted 1924) and the removal of the Sun Dance ban (legalized 1934, via the Indian Reorganization Act) |

| | 1926: founds the National Council of American Indians, for which she was president until her death in . . . |

| | 1938: died; "In perhaps the greatest misrepresentation of a life often misrepresented, she was described in the hospital's postmortem report as "'Gertrude Bonnin from South Dakota—Housewife'" (D&N xxviii)! |

| * WORKS: |

| | 1900: Atlantic Monthly: "Impressions of an Indian Childhood"; "The School Days of an Indian Girl"; "An Indian Teacher among Indians" [all later included in American Indian Stories] |

| |

—Praise(?!) of Zitkala-Ša in an issue of Harper's Bazaar in 1900: "Zitkala-Ša is of the Sioux tribe of Dakota and until her ninth year was a veritable little savage" (qtd. in Fisher vii; see also Helen Keller's letter in the old advertisement in the back of our text). |

| | 1901: book: Old Indian Legends; Harper's Magazine: "The Soft-Hearted Sioux" [later included in American Indian Stories] |

| | 1902: Atlantic Monthly: "Why I Am a Pagan" |

| |

—Carlisle founder Richard Pratt's review of this essay: "its author was 'worse than a pagan'" (D&N xix). |

| | 1913: collaborated with William Hanson on the "Indian opera" Sun Dance (revived on Broadway in 1937 [Fisher]—or 1938? [the year of her death: D&N]) |

| | 1921: book: American Indian Stories |

| | —"[S]he calls her new book the 'blanket book' (the cover image was an image of a Navajo blanket)" (D&N xxvii; note: traditional Indians were often referred to as "blanket Indians"). |

| | —". . . one of the first attempts of a Native American woman to write her own story without the aid of an editor, an interpreter, or an ethnographer" (Fisher vi) |

| | —Her work "lay in some obscurity after her death in 1938 before being rediscovered and reassessed in the 1970s and 1980s" (D&N xiii). |

| * HER TWO WORLDS: |

| | —"Zitkala-Ša had every right to feel nervous about her mission to become the literary counterpart of the oral storytellers of her tribe because she felt compelled to live up to the critical expectations of her white audience" (Fisher vii). |

| | —"To her mother and the traditional Sioux on the reservation . . . she was highly suspect because, in their minds, she had abandoned, even betrayed, the Indian way of life by getting an education in the white man's world. To those at the Carlisle Indian School . . . on the other hand, she was an anathema because she insisted on remaining 'Indian,' writing embarrassing articles such as 'Why I Am a Pagan' that flew in the face of the assimilationist thrust of their education" (Fisher viii). . . . "Zitkala-Ša has been accused of 'selling out' largely because of the difficult balancing act she attempted as a mediator between tribal, bureaucratic, and activist concerns" (D&N xxiv). |

| | —Name change—after quarrel with sister-in-law: "I bore it [the name Simmons] a long time till my brother's wife—angry with me because I insisted upon getting an education—said I had deserted home and I might [as well] give up my brother's name 'Simmons' too. Well, you can guess how queer I felt—away from my own people—homeless—penniless—and even without a name! Then I chose to make a name for myself—and I guess I have made 'Zitkala-Ša' known . . . " (qtd. in Fisher x). . . . Also noteworthy: her brother's (only) given name was actually David; "Zitkala-Ša fictionalized him as Dawée" (D&N xv)! |

| | —Religion: "We can do little more than attempt to keep up with her rapid moves between Catholicism, paganism, Mormonism, and Christian Science" (D&N xv). |

| | —"Though she would spend her life working for the rights of Indians and would become one of the most vocal spokespersons of the Pan-Indian movement in the 1920's and 1930's, Zitkala-Ša was never reconciled with her mother. She spent her life in balance between two worlds, using the language of one to translate the needs of another. She was in a truly liminal ['border'] position, always on the threshold of two worlds but never fully entering either" (Fisher xiii). |

| | —"Controversial to the end, Gertrude Bonnin remained an enigma—a curious blend of civilized romanticism and aggressive individualism. Her own image of herself eventually evolved into an admixture of myth and fact, so that by the time of her death in 1938, she believed, and it was erroneously stated in three obituaries [in major Eastern newspapers], that she was the granddaughter of Sitting Bull . . . though her own mother was older than Sitting Bull [and they weren't even from the same tribe!]" (Fisher xvii). . . . "Zitkala-Ša herself was implicated in propagating this myth. It became one of her favorite autobiographical stories. . ." (D&N xiv). |

| | —"Her career also exemplifies the tremendous difficulty confronting minority people who would become writers but who are constantly under pressure from their own groups to use literature toward socio-political ends. . . . The wonder is that she wrote at all and in so doing became one of the first Indians to bring to the attention of a white audience the traditions of a tribe as well as the personal sensibilities of one of its members" (Fisher xvii-xviii). |

| | —Subversion/"Reinvention"?: [regarding "School Days":] "Resisting the pressures of assimilation in small ways, employing trickster strategies such as vandalizing the school's Bible, she was able to maintain a sense of herself" (D&N xvi). |

| SOURCES: |

| | Fisher = Dexter Fisher's Foreword to the previous U of Nebraska P edition of American Indian Stories |

| | D & N = Davidson & Norris's Introduction to American Indian Stories, Legends, and Other Writings (Penguin Classics) |

| |

| (A more legible/printable version of this handout/outline is on Canvas, in the "ZITKALA-S[h]A" folder.) |

|

** Z-SHA PRE-READING NOTE: I tend to approach longer literary texts—like Z-Sha's three-part autobiography—as a structuralist of sorts,

identifying its building blocks, which I like to call "MOTIFS" (as in musical motifs: snippets of melody or chord progressions

that get repeated throughout the "symphony" that is the text). In Z-Sha, for instance, it's interesting

to follow her DICTION (word choices: e.g., "wigwam," "paleface," "iron horse": WHY? who is her AUDIENCE?); her common FIGURES OF SPEECH

(e.g., the recurring comparisons, implicit or explicit, to "wild animals"); her use of literary conventions

(e.g., those Victorian over-dramatic, emotional moments?!; the Biblical plot motif of temptation & disobedience). Also, speaking of her audience, how might that

have effected her TONE and POINT OF VIEW? How would you characterize her tone (attitude)? How does her tone & PofV

change thru the three sections?

|

|  |

|---|

| TIPI (many Great Plains tribes) | WIGWAM (many Eastern Woodlands tribes) |

|---|

| * "Impressions of an Indian Childhood" [1900] (AIS 7-17) |

|---|

| | I: "My Mother" (7-11) |

| | | —intro setting "exotic" (for her Eastern white audience), a "wigwam" by the "Missouri" (7) [Why "wigwam" [7, 9, 12, etc.] (an Abenaki dwelling/word [northeastern Algonquian tribe]) instead of the Dakota word "tipi" (which she will use later)?!] |

| | | —Mother's characterization (any stereotypes for her audience?): "sad and silent [stoic!]" (yet tearful) (7)—why? |

| | | —Z-Ša's characterization (any stereotypes for her audience?!): a "wild little girl of seven," "light-footed," "free as the wind" and as "spirited" as "a bounding deer"; full of "wild freedom and overflowing spirits" (8) |

| | | —Cousin "Warca-Ziwin" (Sunflower) [Lakota: wahcazizi (wahkCHAHzeezee), "yellow flower"; or wahcazi tanka (wahkCHAHzee TAHNka), "big flower"] |

| | | —Reason for mother's sorrow: the actions of the "paleface" [again note the Western-dimestore-novel word choice (9, 39, etc.)]; Z-Ša's reaction: "'I hate the paleface that makes my mother cry!'" (9) . . . "the paleface has stolen our lands and driven us hither[!—word choice!]"—"like a herd of buffalo" [Native = animal, an eventual motif] . . . and the death of Z-Ša's sister and uncle, upon the tribe's reaching "this western country" (10). [Note: the Dakota were previously inhabitants of Minnesota, mostly, until forced to various reservations in eastern SoDak & NoDak.] |

| | II: "The Legends" (12-17) |

| | | —Indian Ed. 101: Z-Ša hears the "old legends" (13). |

| | | —Emphasis on Dakota "hospitality" towards relatives & friends, especially "old men and women"—and the young's respect, "proper silence" (12-13) |

| | | —"Iktomi story" (15) note: Iktomi is the Dakota/Lakota Trickster figure in the guise of a spider (or "spider-man"); he is the "anti-hero" of many of the stories in Z-Ša's Old Indian Legends. |

| | | —Z-Ša's fearful reaction to the "secret" sign of the "tatooed" "blue star" (16-17; Z-Ša's apparent obsession with this story/image continues in her short story about the "Blue-Star Woman" [159-]). |

|

|---|

|

—Inspired by Lady Gaga's singing of "God Bless America" at the 2017 Super Bowl. (Yes, I know that VD died in 2005!)

|

|

|---|

|

—Relax—it wasn't from this class!

|

TU, Feb. 27th:: TU, Feb. 27th::

| * "Impressions of an Indian Childhood" [1900] (continued; AIS 18-45) |

|---|

| | III. "The Beadwork" (18-24) |

| | | —Indian Ed. 102: bead-making with her mother, whose pedagogical methods seem more Rousseauian than authoritarian—encouraging Z-Ša's own "original designs" (19) and—most of the time—treating her "as a dignified little individual" (20) |

| | | —2nd episode: the girls on their own, "impersonating" their "own mothers" (modeling!) (21-22); but then they give way to their "impulses," shouting and "whooping"—cavorting "like little sportive nymphs on that Dakota sea of rolling green" (22-23; again note Z-Ša's [oddly assimilationist and culturally hybrid] word choices). |

| | | —Chasing her shadow (23-24): a rather predictable & mundane narrative, unless it has further metaphorical resonances? . . . |

| | IV. "The Coffee-Making" (25-29) |

| | | —two separate tales again, of the poor "haunted" fellow (25-26) and Za-S's untoward attempt at hospitality (27-29) |

| | | —Z-Ša's fear of the "crazy man," Wiyaka-Napbina [Lakota: wiyaka (WEE-yah-khah) = feather(s); wanap'in (wah-NAH-p'ee[n]) = necklace)], whom her mother says really should be pitied, having been "overtaken by a malicious spirit" (25-26) |

| | | —Z-Ša's coffee-making = "muddy warm water" for the visiting old man (27-29)—and the others' polite respect for her efforts, nonetheless: "But neither she [her mother] nor the warrior, whom the law of our custom had compelled to partake of my insipid hospitality, said anything to embarrass me" (28). |

| | | —NOTE: "How!" (28) now more commonly (and less confusingly) spelled "Hau!"—Lakota/Dakota word of both greeting ("hello") and assent ("you betcha"). |

| | V. "The Dead Man's Plum Bush" (30-33) |